Chemotherapy rewires gut bacteria to curb metastasis

22 January 2026

0 comments

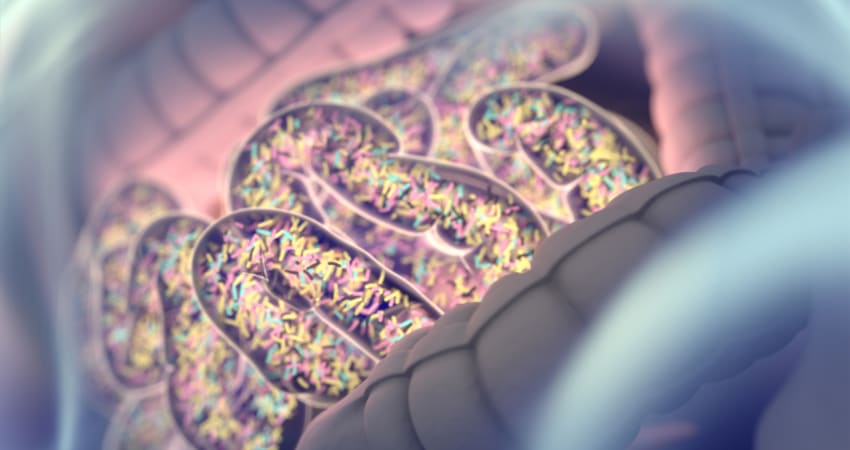

Credit: Getty Images/ChrisChrisW

Credit: Getty Images/ChrisChrisWBy Olivia Bowthorpe

Chemotherapy does more than kill cancer cells – it may also rewire the body's defences to stop cancer spreading in the first place.

A new study has uncovered an unexpected chain reaction: chemotherapy damages the gut lining, altering the microbiota, a well-known side-effect. This triggers bacteria to then produce a compound that travels through the bloodstream to the bone marrow, priming the immune system to attack metastases more effectively, say researchers.

You might also like